Miniatures

I

I look through a circular window:

I make a frame of small twigs with budding leaves;

Inside this the first spring skippers are jumping:

Yellow and pink, yellow and pink.

The soundless rhythm of their feet jumping

Becomes visible as bubbles on this cup of tea.

II

The grass-seed sower casts, casts,

And behind her the birds come

Greedy for her hopes. They are eating up

This poem almost as quickly as I can make it.

III

The long-legged man is again whistling

As he goes early to work. Seen

Through a basement bedroom window,

he will always be recalled by boots and jeans,

and the whistling that encircles him completely

in his day’s dancing.

IV

Anne Brontë’s grave is planted completely

and mysteriously: “No one knows who tends it.”

This time it is lined by yellow pansies,

and fixes (for a short spell),

our hammered-by-the-sea-winds straying thoughts.

V

“The little island of the year,” my mother says

and so from desert island it grows;

populated by family: Family Reunion. Disquiet

about estrangement motivates roots-out-of tumbleweed:

annual habitation (strangely)

magnets from a tiny stamp or the kiss

that fixes it on the ‘just-a-reminder’ postcard.

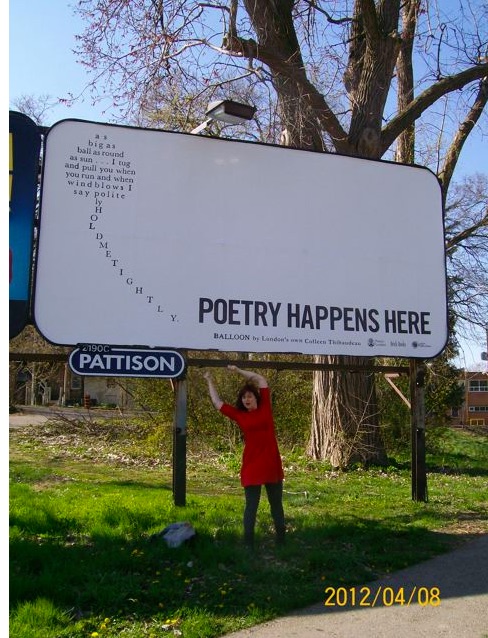

Colleen Thibaudeau, 1991

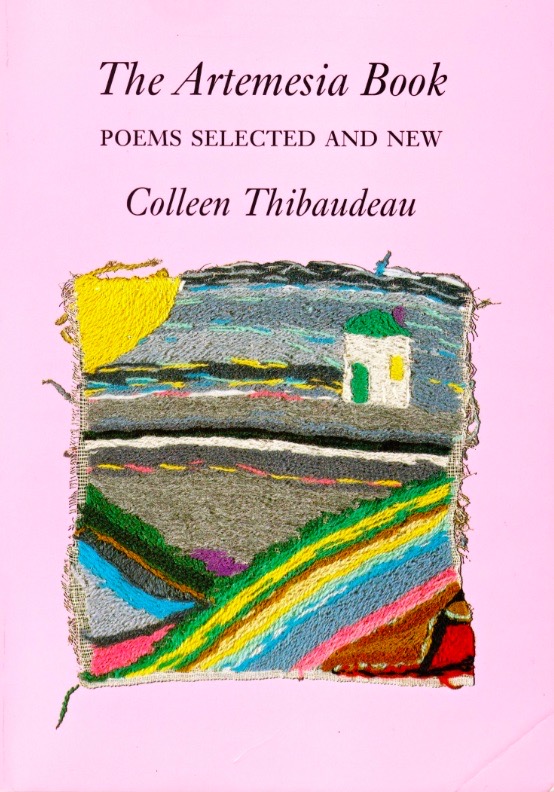

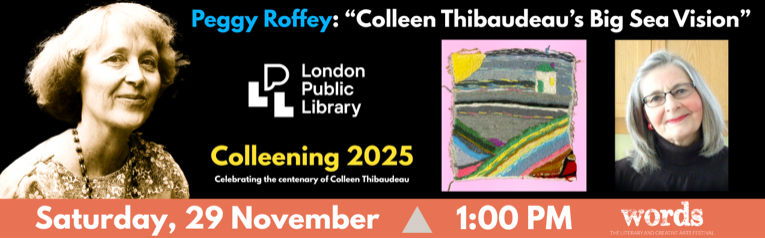

“Miniatures” is from The Artemisia Book (1991), available from Brick Books. The poem is also included in AlvegoRoot Theatre’s play Colleening: The Letters and Poetry of Colleen Thibaudeau from November 2025.